Stories impose shapes on the world. Narrative emerges out of a process of selective attention – of extracting a salient structure of events out of chaotic complexity, of choosing one path out of innumerable possible ones through the forest. From Aristotle to contemporary philosophers, literary critics and anthropologists, the identification and grouping of narrative shapes has been a problem that has continued to fascinate. Data scientists are only the latest addition to the long tradition of intellectuals intrigued by the shapes of stories.

This is the first part of what I hope will turn into a series of quantitative and computational explorations of plot. In this introduction, we will begin by exploring how qualitative ways of thinking about plot might help our approach. For the technical details of building the graphs, see part 2.

Use the slider to adjust links:

Aristotle’s declaration in his Poetics, that a plot should have a beginning, a middle, and an end might seem childishly obvious, but highlights a crucial point – that we tend to think of narrative as events unfolding in time. Of course, the kind of events that unfold in time matter hugely in creating the proper effect of the narrative. In fact, Poetics is a detailed elaboration of this for one particular kind of plot – tragedy. But nevertheless the chronological order of the unfolding of events is a key element of our understanding of plot. My favorite Shakespearean example of this is to compare Othello to a conventional comedy like As You Like It. Othello begins with a marriage, ends with several deaths and the utter collapse of the protagonist’s world. As You Like It, on the other hand, begins in crisis following a death but eventually finds its way to harmonious resolution and ends with a bunch of marriages. Both plays deal with roughly analogous themes – love, loyalty, friendship, trust – the little individual things that add up to the foundation of social order. But how these elements are arranged in time makes one a tragedy and the other a comedy. To ignore the order of arrangement of these events – as one might, for example in a text-analysis approach that turns an entire play into a bag-of-words – might reveal that they share many linguistic and thematic similarities, as has been demonstrated in a fascinating study by Jonathan Hope and Michael Witmore,1 but make us miss the crucial fact that the arrangement of these events makes them very different kinds of narrative.

Over the last century or so, the question of plot shape has continued to draw attention. In the early twentieth century, the school of critics known as the Russian Formalists spent considerable time discussing plot, the exemplary work here being Vladimir Propp’s wonderful book The Morphology of the Folk Tale. Anthropologists from Levi Strauss to Pierre Bourdieu, and literary theorists from Roland Barthes to Gérard Gennette have written about narrative in terms of what they call “structure.” The most familiar among such discussions of plot might be Kurt Vonnegut’s entertaining lecture on the topic where he visualizes the shapes of stories as a kind of sentiment graph where time is plotted on the X axis and the Y axis represents positive or negative sentiment score. Not only is Vonnegut’s exploration rather amusing and engaging, it might especially appeal to data-scientists. In fact, Matthew Jockers has used sentiment analysis to realize Vonnegut’s insight and extended it in fascinating ways. Such a model of plot as essentially a time series of sentiment scores has the great virtue of retaining the Aritotelian dictum of development through time and an understanding of plot as a function of emotion – which, after all, is the most immediate way we engage with narrative. We dread bad outcomes, and anticipate good ones. We cheer for heroic characters and root against the bad guys. We shudder at crisis and revel in their resolution.

But there is perhaps another element to plot that eludes this purely chronological unfolding of sentiment and might supplement our understanding of it. And most contemporary thinkers about narrative – including the “structuralists” mentioned above – have tried to approach what we might think of as this non-linear quality of plot. Think about it: if you hear the title The Tragedy of Macbeth, you immediately know the rough chronological shape of the story: things are going to start out relatively okay, there’s going to be some kind of massive crisis and downfall, and a bunch of people are going to end up dead. It’s all going to be very sad. But there is obviously more to Macbeth than the raw outline of the plot (which Shakespeare borrowed from elsewhere anyway). It is the interplay of character and language and motif and imagery – in other words the countless little building blocks at the disposal of the author – that are combined in particular ways to give plot its proper affect.

The Art of Storytelling: From Chronology to Symbolic Space

The concept of structure pays attention to dimensions of plot other than its purely chronological shape and tries to incorporate thematic elements that organize and shape the reception of the sequence of events. In other words, it tries to capture dimensions of narrative that don’t work chronologically but rather takes the form of accumulative world building. Obviously when we read or watch stories unfold – in books, or theater, or film – we consume the text in a linear manner. But narrative can resist this simple linearity in multiple ways. Flashbacks, and non-linear representations of time are one set of obvious ways to do it. But I would argue that even when a story is being told perfectly chronologically, the text invites us to organize its narrative in a kind of symbolic space. We notice character associations, thematic elements, ethical perspectives etc. To return to the example of Macbeth, we would miss crucial elements of the narrative if we reduced it to a mere chronological ebb and flow of sentiment. It would be like having a really bad storyteller narrate the plot of the play as a series of events – Macbeth meets the witches, then Duncan, then his wife etc – without inviting us to actively participate and build a set of mental connections. And Shakespeare is far from a bad storyteller.

Generations of critics have discussed how the plot of a play like Macbeth “works” – how it produces certain affects, how it invites us to pay attention to certain things. We read the play – one might even say that the play compels us to read it – by supplementing the chronological unfolding of narrative with other elements. We draw associations. We make connections and comparisons. When Macbeth is named Thane of Cawdor by Duncan’s messengers this is not an isolated event. In fact, it only takes on its significance in the narrative because it refers back to the witches’ prophecy, and Banquo’s very different reaction; it also reveals and anticipates Macbeth’s ambition and conflict. When Lady Macbeth admonishes her husband for his infirmity of purpose, it is not sufficient to note the fact that she is overly ambitious and somewhat domineering. Shakespeare’s language leaves clues for us. She might or might not jump out as the “fourth witch” for every reader, but the fact that she is a catalyst spurring on the struggle between allegiance and ambition unfolding in Macbeth is undeniable. In other words, at every moment the narrative is self reflexive, it doesn’t merely proceed through time, it folds back on itself, it looks forward. It sets up effects for us to notice, tensions to resolve later. In short, it invites us to participate in building the world of the play.

Plot, therefore, is as much a contour in symbolic space as it is a time series. Aristotle observed that while plot dictates character, in great drama it emanates out of character. If an author is in perfect control of characters, their natural interactions will give rise to the machinations of plot.

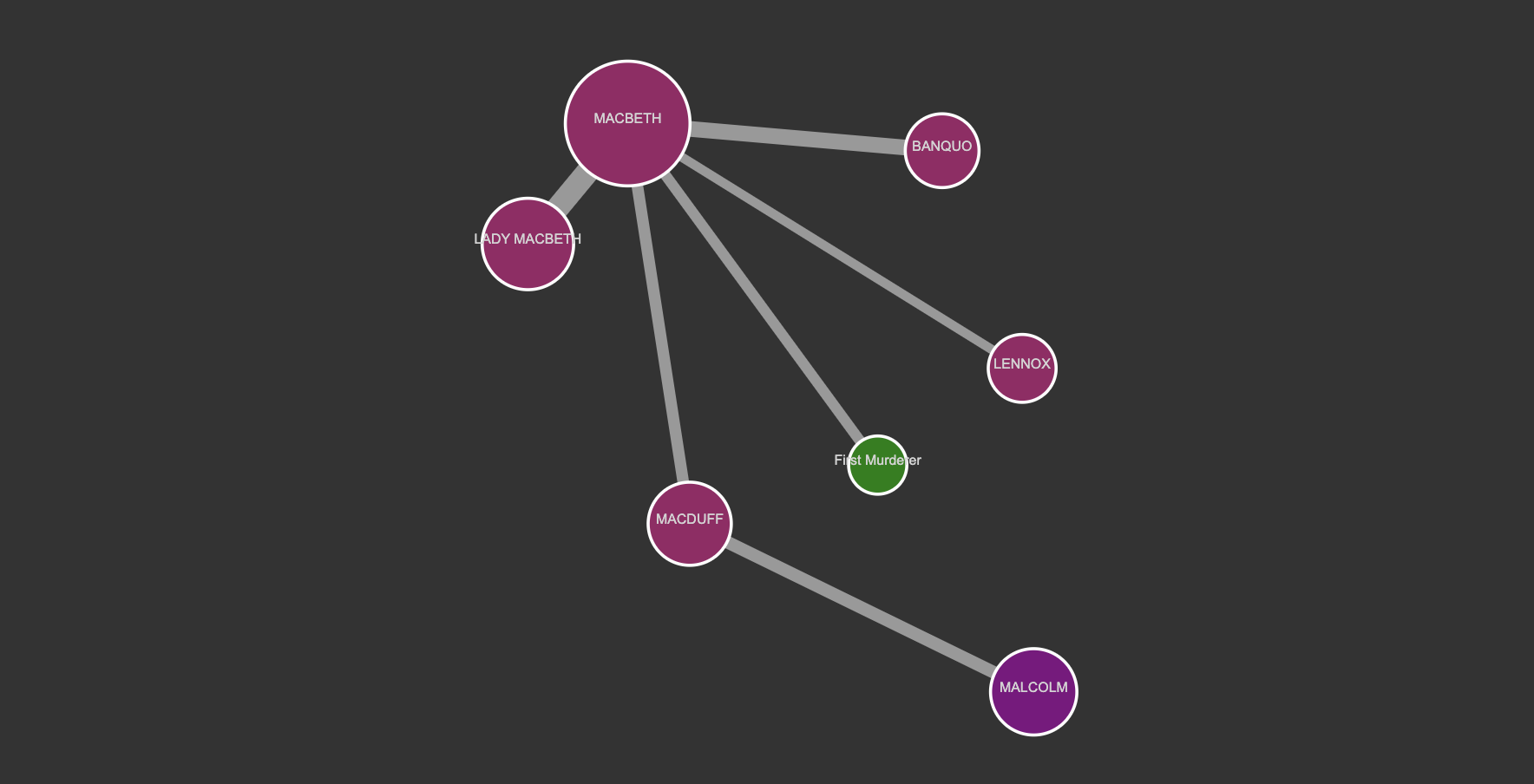

A network perspective invites us to think of narrative within such symbolic space, beyond the strict tyranny of chronological unfolding. It is as if Shakespeare puts these characters one by one in front of us, and invites us to build the network of their interactions to truly appreciate the structure of the play. In the second part of this series, I will describe the technical details of how these networks were built and turn my attention to some really interesting recent work on networks as a mode of thinking about plot. But if you play around with the network above, notice how the entirety of a play starts out as a jumble of interactions. Color by gender and notice that apart from the innocent Lady Macduff, how Macbeth is surrounded by female figures who draw him into what he calls “the river of blood.” Then, as you start to strip away the less important connections (use the slider) Macbeth and Lady Macbeth are left all alone by themselves – lady Macbeth intensely lonely and isolated, cut off from everyone else and driven to insanity; and Macbeth surrounded with enemies closing in and the ghosts of those he has killed.

-

Jonathan Hope and Michael Witmore, “The Hundredth Psalm to the Tune of ‘Green Sleeves’: Digital Approaches to Shakespeare’s Language of Genre,” Shakespeare Quarterly 61, no. 3 (2010): 357–90. ↩